Main content

Top content

Public Goods

- What kind of goods are there?

- Who buys the public good?

- Free rider behaviour in the experiment

- How can (more) people be persuaded to make (higher) contributions to public goods?

- The financing of public goods through taxes

- Climate change - what does it have to do with public goods?

- Links and downloads

Experimente zum Thema

- Public goods and free riders

- Tax financing of public goods

- Overcoming free-rider problems

- Insurances

Hinweis Glossar:

Some terms are explained in our Glossary

(in progress)

What kind of goods are there?

There are different differentiation criteria for goods, such as the distinction between physical goods (food, clothing, ...) and services (train journey, concert attendance, ...). This Economics Works topic is about a different distinction, namely according to the criteria of so-called rivalry and exclusivity. Rivalry means that not an unlimited number of people can use the same good equally and at the same time. This applies to food or clothing, for example, but also to every other physical good and most services. Excludability means that people can exclude other people from using the good. Excludability is a consequence of private ownership of a good, but excludability does not apply to public paths or parks, for example.

This topic focuses on goods for which there is no exclusivity. Depending on the degree of rivalry, they are called common goods or public goods. In its pure form, a public good is a good for which there is no rivalry at all. Such goods cannot be physical goods because the resources to produce them are limited. Therefore, when looking for examples of public goods, people often cite services that are quickly taken for granted because they are not perceived as such, e.g. public safety. But strictly speaking, the following also applies here: there is rivalry because, for example, the police cannot provide the same level of security everywhere at the same time. So even for goods for which there is no exclusivity, there is usually rivalry. One example is a city park: it is open to all citizens, but cannot be used by everyone at the same time (unless it is very large!).

Public goods that are always at risk of being over-utilised are called common goods. The term commons stands for ‘what belongs to everyone’ and thus for a communal form of management. A forest that the surrounding inhabitants use by collecting firewood, felling trees or hunting animals is a common good: if it is overused, its value is reduced or even its existence jeopardised. The same applies to other natural resources such as bodies of water or grazing land. In the following, we will continue to speak generally of ‘public goods’. However, it should have become clear that these are often common goods.

Who buys the public good?

The fact that public goods are non-excludable leads to a problem: individuals can use the good without paying for it. But who then pays for the public good, who ‘buys it’?

Example

Let's look at a simple example: There are street lamps in a residential neighbourhood that provide light at night, making residents safer: Accidents are avoided and dangers can be recognised earlier. Every resident of the street therefore benefits from the streetlights. At the same time, no one can be easily excluded from the light of the lantern. Let's imagine that the majority of residents recognise the benefits of street lamps and therefore think it makes sense for them to be installed on the streets.

Let's imagine that the residents of the street get together one evening and discuss the purchase of the lanterns. One suggestion could be that all residents should bear an equal share of the costs. However, the residents' association cannot force each individual to contribute, and it is therefore possible that too little money is collected because some do not want to pay at all and others do not want to pay as much as necessary. Residents who do not want to pay would use the property without contributing; this behaviour is called free-riding.

The opportunities for free-riding would very often lead to public goods not being provided. And this despite the fact that (we assumed) the community would benefit from the provision of public goods.

Free rider behaviour in the experiment

Whether and under what conditions people are willing to contribute to the provision of public goods or are free riders has been the subject of intensive research in economics. Economic experiments have also been used for this purpose.

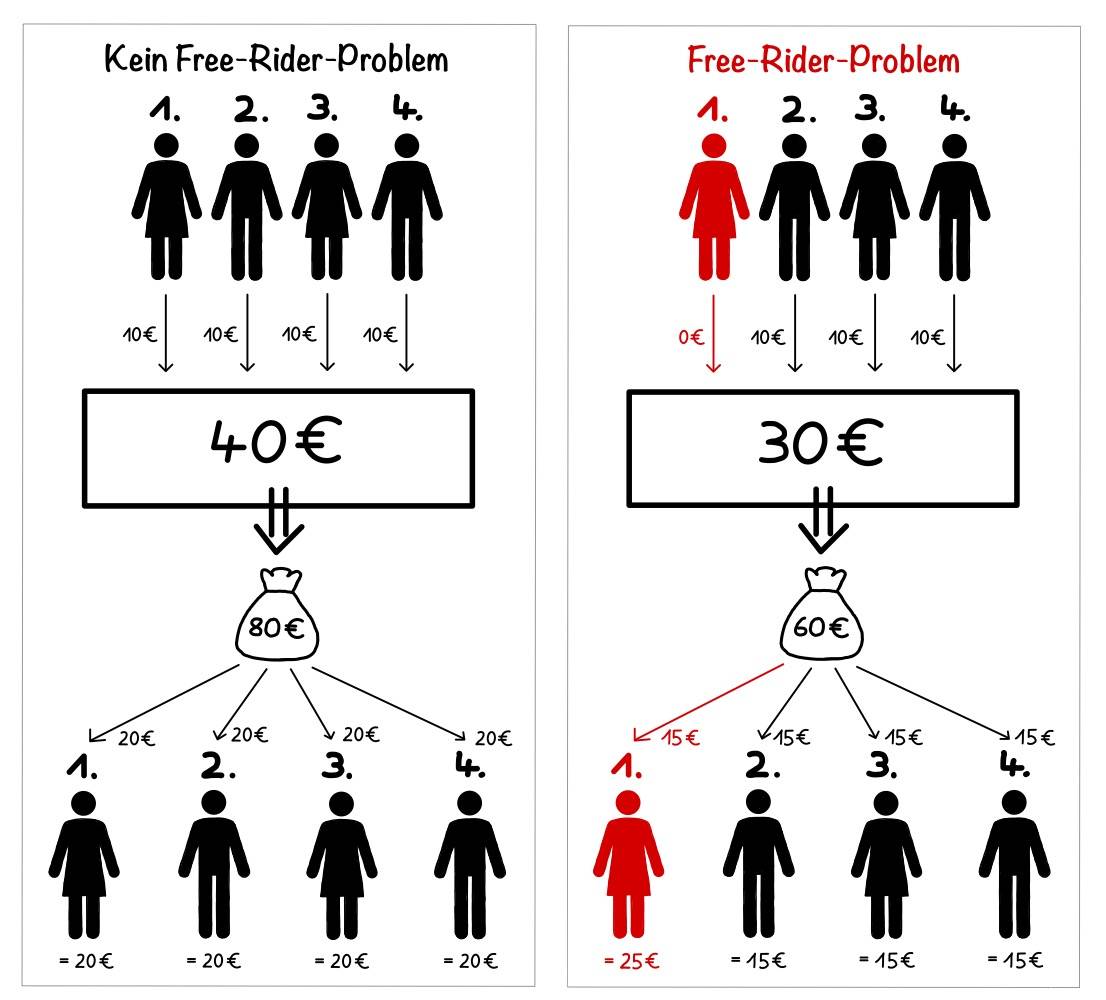

The first experiment on the topic of public goods corresponds to the classic experiment from research. It is called the Public Good Game and has the following simple rules: Four participants each form the ‘community’, which collects money to finance a public good. Each participant has an equal initial budget of 10 euros. The fact that providing the public good is advantageous for the community is illustrated in the game as follows: Each participant can pay into a ‘pot’. The total amount paid into the pot is doubled, after which the amount is distributed back equally to all four participants. So if all four were to put the full 10 euros into the pot, 4 * 10 = 40 euros would come together and be doubled in the pot to 80 euros, so that everyone ends up with 80 / 4 = 20 euros. All participants decide at the same time how much they want to pay into the pot without knowing what the others are doing.

The game clearly shows the potential advantage of free-riding, as each individual can benefit from not paying into the pot themselves. For example, if three of the four people paid in the full €10 and one person paid nothing, there would be €60 in the pot at the end. The picture on the right illustrates the situation. In the picture, the first person ends up with 10 + 1/4 - 60 = 25 euros, while the other three only have 15 euros. This solution is worse for the community than a situation in which everyone gives the full 10 euros, as in the left-hand picture. This is because in the picture on the right, all four together end up with only 70 euros (25+15+15+15), not 80 euros as in the picture on the left. Free-rider behaviour is a so-called dominant strategy in the experiment: regardless of how much the others pay into the pot, your own advantage is always greatest if you give nothing. However, if everyone thinks this way, nothing ends up in the pot, which is the worst situation for the community as a whole.

Results from research experiments show that experiment participants invest an average of around 50% of their budget in the public good. So there is free-rider behaviour. But there is also cooperative or ‘social behaviour’, i.e. contributing to the public good. While free-rider behaviour can be explained by the homo economicus model, (other) socio-psychological theories explain cooperative behaviour. For example, people follow social norms and contribute to the public good because they simply think it is the right thing to do. However, research experiments have also shown that contributions to the public good decrease over time, i.e. when the game is repeated several times. This observation can be explained by the fact that the participants behave reciprocally, according to the principle of ‘tit for tat’ and react to the free-riding of others by also no longer cooperating.

How can (more) people be persuaded to make (higher) contributions to public goods?

Research experiments have also investigated the question of which mechanisms can be used to ensure that experiment participants cooperate better, i.e. contribute more to the public good. One simple ‘mechanism’ is to get the people involved ‘round the table’. Talking to each other is usually beneficial, even if the agreements reached at the table are not binding and each person involved can still ride the freewheel afterwards.

One powerful mechanism is to give members of the community the opportunity to reward or punish each other. Experiments show that the opportunity to punish free-riding in particular increases the willingness to cooperate. Rewarding cooperative behaviour also helps, but has a smaller effect than punishments.

Another mechanism could be that people from the community decide how much they contribute to the public good one after the other, rather than simultaneously.

In a variation of the experiment on public goods, the four people in the group decide in turn how much they will put into the pot. Each participant sees how much their predecessors have given before deciding for themselves.

Knowing how many others contribute to the public good provides orientation for people who want to behave cooperatively. These people can copy the behaviour of others (i.e. give just as much as the others before them). As a result, the behaviour of the people who start is critical for the outcome: if a homo economicus starts, nothing is contributed at the beginning, and this behaviour may then be taken as a model by others, so that cooperation does not occur.

The financing of public goods through taxes

A situation in which too few people in a community are willing to contribute to the financing of public goods is characterised by a market failure: the people involved do not succeed in creating a situation that makes everyone better off. The term market failure stems from the fact that no (state) authority intervenes in the situation under consideration and forces the provision of the public good. This intervention by the state authority takes the form of compulsory levies, the most important of which are taxes. Taxes are levied by virtue of the state's financial sovereignty without those who pay taxes being entitled to anything in return. Public goods are regularly financed by taxes. However, taxes do not have a good reputation among most citizens. Too high, too many, too complicated: this is a simple way of summarising many people's opinion of taxes. The consequence of this negative attitude towards tax-based financing of public goods is tax avoidance behaviour: People try to save on taxes. They have every right to do so, as this is not about illegal measures (such as tax fraud), but rather, as one of the bestselling guidebooks puts it, ‘1000 completely legal tax tricks’.

In another version of the experiment on public goods, the four people again decide simultaneously how much to put into the pot. However, this decision is made in the form of a ‘tax return’: The participants* do not put money directly into the pot, but instead state in their ‘income tax return’ what income is to be taxed. The tax rate is 50%, so a participant puts €5 into the pot if they state that they pay tax on €10. However, as in the basic experiment, this information is a free decision by the participants.

(picture still missing)

In the experiment, all participants can pay or avoid taxes equally. In reality, however, things are very different: the options for avoiding taxes vary greatly depending on the type of income. Internationally active companies in particular have far-reaching opportunities to reduce their tax burden, which ultimately benefits the owners of these companies.

Climate change - what does it have to do with public goods?

Climate is a public good: no one can be excluded from the effects of climate improvement or climate deterioration. If we look at the problem of climate change from the perspective of governments or states, then there is also the free-rider problem here, because an individual government can allow other states to ensure a better climate while doing nothing itself or even pursuing climate-damaging strategies (e.g. promoting the burning of fossil fuels). The community here is the international community of states, and again, the community is harmed by free-rider behaviour if the consequences of climate change outweigh the costs of measures to combat it in good time.

However, unlike in a good neighbourhood, where it is possible to get enough donors together for street lamps, it is much more difficult for the international community of states to conclude binding agreements on reducing CO2 emissions, for example. This is also due to the diversity of states, not only in terms of their political systems, but also in terms of their economic power and their dependence on the availability of large quantities of energy and raw materials. However, climate agreements are designed in such a way that a large number of countries participate, and this usually leads to compromises being agreed that fall short of important climate targets.

The mechanisms that can be used to encourage people to contribute to the financing of public goods can also be applied (to a limited extent) to the climate issue. For example, smaller groups of states could form coalitions that set themselves more ambitious targets. These coalitions would then have a pioneering role in the fight against climate change. If these coalitions have sufficient political and economic influence, they can persuade other countries to change their thinking. Studies show that investments by pioneering states in climate protection ‘infect’ other states: if an influential government sets a good example, the others follow suit - unfortunately, the same applies to ‘leading by example’.

Links and downloads

Here you will find our Glossary

Here you can get the right Student text

Here you come to the Experiments

Here you will find Materials for further Discussion

Here you can find the used Literature